"Everything in life is

vibration"Albert Einstein COLOR THERAPY

In colour there is life. To understand this

power, is living. Our most important energy source is light, and the entire spectrum

of colours is derived from light. Sunlight, which contains all

the wavelengths, consists of the entire electromagnetic spectrum

that we depend on to exist on this planet. We know that each colour found in the visible light spectrum has

its own wavelength and its own frequency, which produces a specific

energy and has a nutritive effect. We know some rays can be dangerous

if we are exposed to them. But the visible light, the rainbow,

has a soothing effect on us. Our body absorbs colour energy through the vibration colour gives

off. All organs, body systems, and functions are connected to main

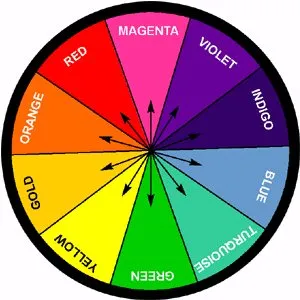

energy centres. Light consists of the seven colour energies: Red, Orange, Yellow,

Green, Blue, Indigo, and Violet. Each colour is connected to various

areas of our body and will affect us differently emotionally, physically,

and mentally. By learning how each colour influences us, we can

effectively use colour to give us an extra boost of energy when

we need it.

BRIEF HISTORY OF COLOR AND LIGHT THERAPY Healing by means of color and light was the first type of therapy used by man. The sun's rays kept him warm, the colors of the flora fed him and accounted for his mood. The Egyptian Pharaohs and the Inca Indians worshipped the Sun as God and used plants as medicinal herbs. In 6th century BC, Orpheus, the founder of the first metaphysical mystery school in Greece utilized vibrational medicine of color and light as a means of healing and spiritual awareness. Both Pythagorus and Plato were strongly influenced by his teachings. In 125 AD - the ancient scientist, Apuleius experimented with a flickering light stimulus used to reveal epilepsy. In 200 AD - Ptolemy observed patterns of color rays coming from the sun into the eyes produced a feeling of euphoria. In the 17th century - French psychologist Pierre Janet used flickering lights to reduce hysteria for hospital patients. 1876 - Augustus Pleasanton used blue light to stimulate the glandular system. In this same year, Seth Pancoast utilized red light to stimulate the nervous system. 1878 - Dr. Edwin Babbitt used variant colors to produce healing of internal organs. 1908 - Aura Soma developed in England used colors to heal physical and emotional symptoms and promote psychological change. 1926 - C.G. Sander specified that application of particular colors was necessary for normal health. 1930 - The Father of Spectro-Chrome Metry, Dinshah P. Ghadiali compiled an encyclopedia of treatment with the use of color and light for over 400 various health related disorders. 1941 - Dr. Harry Riley Spitler formulated "The Syntonic Principle" stating that light by way of the eyes balances the autonomic nervous system. 1943 - Dr. Max Lucher developed psychological color testing to reveal information hidden in the subconscious mind which is still used today. 1980 - Dr. Thomas Budzynski - used phototherapy to accelerate learning. 1991 - Dr. Harrah Conforth applied color and light to facilitate whole brain synchronization and Dr. Robert Cosgrove utilized colored light for sedative properties prior to , during and immediately following surgery. george star white

Color Research Physical healing is encouraged by directing colored light towards diseased areas of the body or to the eyes. In conventional medical treatment, phototherapy and photochemotherapy are used in current dermatological practice e.g. in the treatment of psoriasis, and blue light has been shown to be effective in the treatment of hyperbiliruminemia in the newborn. There is a wealth of evidence to support the psychological effects of color and Dr Max Luscher's The Luscher Color Test contains ample evidence of this (be advised that many of the references in this book are in German). In conventional medical practice, the use of blue light in the

treatment of hyperbilirubinemia has been proven by many researchers

including Vreman et al with their study "Light-emitting diodes:

a novel light source for phototherapy". Creamer and McGregor of

St John's Institute of Dermatology, London. UK published a paper

in January 1998 entitled "Photo (chemo) therapy: advances for systemic

or cutaneous disease", exploring the value of light as a treatment.

Griffiths of the University of Manchester, UK, in July 1998, published

a paper on "Novel therapeutic approaches to psoriasis" and in October

1998, The Archives of General Psychiatry ran four articles on light

therapy. Regrettably, where treatment of a broader spectrum of

disorders is concerned, the evidence is largely anecdotal. 1. In 1997 researchers at the School of Agriculture and Forest Science at the University of Wales, UK used red and blue light to establish whether these would increase activity and reduce locomotion disorders in meat chickens. They showed that in 108 chicks walking, standing, aggression and wing stretching all increased in intensity when reared from day 1-35 in red light. Where blue light was used, there was a high incidence of gait abnormalities. Prayitno DS., Phillips CJ and Stokes DK. 1997. The effects of color and intensity of light on behaviour and leg disorders in broiler chickens. Poultry Science 76(12): 1674-81. 2. Michael Kasperbauer, a researcher at the US Agricultural Research Service Center in Florence, South Carolina, showed that using red plastic sheeting under tomato and cotton plants produced a 15-20% higher yield than plants grown over traditional black or clear plastic. Also turnips grown under blue plastic had an improved flavour when compared with those grown under green sheets. Analysis of those grown under the blue plastic revealed that they had higher concentrations of glucocinolates and vitamin C (glucosinolates being the compounds which give turnips and horseradish their traditional "bite"). Kasperbauer and his team have also investigated the link between color and pest control. Michael Orzolek of Pennsylvania State University proved that aphids and the plant viruses they transmit are generally attracted to yellow and repelled by red and blue. This finding echoes the work of Babbitt a century earlier when he wrote "The electrical colors which are transmitted by blue glass often destroy the insects which feed upon plants." Boyce N. Rainbow Growing. New Scientist. 24 October 1998. Future research could focus on the clinical efficacy of color

therapy and, the neurobiological mechanism of action. Extensive

anecdotal evidence of the value of color therapy in the treatment

of countless physical disorders over many decades deserves to be

revisited. However, this evidence needs to be subjected to rigorous

scientific research in order to establish (or otherwise) a sound

basis for color therapy. Developing instruments for applying color

could provide a commercial incentive for clinical trials.

The practical application of a specific colour for a bodily condition

requires common sense and experimentation. Generally, dis-harmony

that produces a cold, wet condition requires red. Conditions of

a hot, thermal nature require blue to calm and effect a stabilization

of the subtle body in question. Therefore, contra-indicated to

any red condition is the use of a red colour application such as

with sunstroke. The use of red will aggravate the problem. The

same is true of any blue condition; ie, contra-indicated for colds

or pneumonia is the use of cold blue.

The general rule of thumb is to place the affected area 12 inches

from the glass and approximately 10-12 inches from your LIGHT SOUIRCE

if you are inside. Twice a day is the ideal and, once started,

the treatment should continue until the complaint is gone. TIMES RED: 5-10 minutes. Never more than 10 minutes. Any colour that is applied to a specific area must be localized; this is very important. Green, yellow and blue may be general. Red is never to be applied to the head region. The best part of the

rainbow isn't the pot of gold... " An apple reflects a shade of red to the retina,

forming impulses that travel as coded messages to the brain,

where hormones are released, altering metabolism, sleeping, feeding

and temperature patterns. So you see, we don't just notice colors,

we feel them. Mentally, physically, emotionally and spiritually,

they empower us. Dawn to dusk, they rule our world, transforming

nature's energy into personal realization. Every color has its

own personality and in each lies knowledge and clarity."

Color Therapy, or Color Healing, is the therapeautic use of varous

forms of color and light for physical, emotional, and spiritual

benefit to the human body. Color and light therapy involves the

application colour in a variety of ways: colored gels with light

to penetrate and stimulate the body's meridians which corresponds

to traditional Asian acupuncture systems as well as accessing and

incorporating the axiational lines ; colored lights applied to

areas of the body; the use of colored lenses (prescription and

non-prescription eyewear) for a variety of health concerns; the

use of the sun; light applied to the eyes ; and the use of crystals

or crystal rods with or without an outside light source for penetration

of colorinto the body through the auric field, also using the acupuncture

systems and axiational lines. Further use of color is made in the

environment through the use of colored light bulbs, the paints

applied to a room, the color of carpeting and furniture, or through

the use of certain colored clothes, the use of crystals in the

environment, sunlight, all of which directly impact the body through

the bio magnetic (auric) field.

The condition that led the way to acceptance of some form of light treatments is Seasonal Affective Disorder or S.A.D.. This condition occurs most frequently during the long winter months but has also been shown to be present in people who have been house or hospital confined for long periods. Other occupations, such as pilots, flight attendants, miners, third shift industrial workers, etc., also experience symptoms of light deprivation. Some of these industries have begun to require the employees to sit in full spectrum light rooms for periods of time to avoid symptoms. Some people have affectionately called this condition "Cabin Fever" and have used it to describe a feeling of frustration, confinement, irritation at everything and anything and an inability to concentrate or enjoy the simple pleasures of life. " All forms of matter are

really light waves in motion." Color. We delight in a rainbow, sigh at a sunset, luxuriate in the rich colors of our homes, clothes, special spaces. Our eyes gravitate towards saturated color like moths to the light. No coincidence, considering the entire spectrum of colors is derived from light. And no surprise, really, that seeing, wearing or being exposed to color- whether in the form of light, pigment, or cloth- can affect us at levels we are only just beginning to understand. Scientifically, it makes sense. Color is simply a form of visible light, of electromagnetic energy. Let's break it down. What exactly is light? It is the visible reflection off the particles in the atmosphere. Color makes up a band of these light wave frequencies from red at 1/33,000th's of an inch wavelength to violet at 1/67,000 of an inch wavelength. Below red lie infrared and radio waves. Above it: the invisible ultraviolet, x-rays, and gamma rays. We all understand the impact of ultraviolet and x-rays, do we not? Why then wouldn't the light we can see "as color" not have as big an impact? How we "feel" about color is more than psychological. The last decade has proven that lack of color, or more specifically, light, causes millions to suffer each winter from a mild depression known as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). Because of the complex way in which exposure to various colors acts via the brain upon the autonomic nervous system, exposure to a specific color can even alter physiological measurements such as blood pressure, electrical skin resistance and glandular functions in your body. And they most certainly can affect how you feel on a day-to-day basis. Learning about color's qualities and putting it to use can enhance your spirit, improve your health, and quite ultimately, expand your consciousness. Did you know? In Occult Meditation, by Alice A. Bailey, the Tibetan says that "..colours are the expressions of force or quality. They hide or veil the abstract qualities of the Logos, which are reflected as virtues or faculties. Therefore, just as the seven colours hide qualities in the Logos, so these virtues demonstrate in the life of the personality and are brought forward objectively through the practice of meditation; thus each life will be seen as corresponding to a colour." The basic premise of the ancient art of Colour Therapy is that all manifested life is energy, emanating from One Source, to and including all directions, encompassing all possibilities. It is here that we begin to see just why colour and sound play a very important part in our everyday lives. Each day we see colours and hear sounds which act upon our bodies. When we find a colour or ray quality lacking or in excess, the result can be dis-ease, dis-harmony or dis-cord. The modern interpreter of colour therapy, or chromo therapy, was Dr Edwin Babbitt with his widely known work The Principles of Colour Therapy, printed in 1878. It is interesting to note that Babbitt's diagram of the atom is found in A Treatise on Cosmic Fire by Alice Bailey. The Tibetan illustrates that this energy system is repeated throughout the manifested universe, from the smallest atom up to and including the largest solar system. Here again we find agreement between exoteric and esoteric scientific theory. In meditation, you may visualize or 'breathe in' a specific colour for treatment of any conditions previously named. By consistently practising this form of colour therapy, you will achieve the desired result, though the time period may be slightly longer. As we have seen through example and experiment all is Energy and that Energy generates a force which is applied either correctly or not. In the correct apprehension of force and its action upon our bodies, we can truly effect lasting change within ourselves. "Colour is therefore 'that which does conceal'. It is simply the objective medium by means of which the inner force transmits itself; it is the reflection upon matter of the type of influence that is emanating from the Logos, and which has penetrated to the densest part of His solar system. We recognize it as colour. The adept knows it as differentiated force, and the initiate of the higher degrees knows it as ultimate light, undifferentiated and undivided." - The Tibetan. This ancient art is still practical today, and its uses are many and varied. As John Gage shows in his definitive history Colour and Culture (1995), the way we see colour is associative rather than empiric – for example, we think of blue as cool, expansive and soothing, even though the blue bit of a gas flame is hotter than the orange. Colour has different meanings in different contexts, but, Gage writes, “there seems to be a universal urge to attribute affective characters to colours”. Practitioners of chromo-therapy were convinced that colour was primarily a question of immediate feeling rather than intellectual judgment, and that it could have profound psychological and physiological influences. This belief in the powerful corporeal effects of colour influenced avant-garde artists such as Gauguin and Kandinsky, who thought of chromo-therapy as a useful tool in developing a non-representational art, because it provided the grammar for a supposed universal language of colour. But though chromo-therapy was once an intellectual fashion, its role in the story of modern art is largely forgotten. Where did the idea that colour could heal come from? In the West, theories of colour evolved out of alchemy and medicine; colour was, therefore, intimately bound up with the therapeutic. The first colour circles were urine charts used by physicians to identify an imbalance of the four humours. A fifteenth-century example, from an anonymous Treatise on Urine, shows a radial pattern of twenty vials in various hues, running from clear (indicative of a phlegmatic temperament) to black (melancholic) through a series of yellow ochres (choleric) and blood reds (sanguine). Potions and herbs were often chosen by doctors on the basis that their colour opposed and would therefore harmonise any humoural lopsidedness.

In his influential Theory of Colours (1810), Goethe developed this relationship between colour and Hippocratic medicine. He and his friend, the Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schiller, also visualised colour relationships in a circle – which they called a “Temperamental Rose” – but they adapted the entire spectrum (not just those shades relevant to the medical diagnosis of bodily fluids) to the four humours. Green and yellow represented the active, sanguine character, exemplified by bon vivants, lovers and poets. Purple and blue-red characterised the passive and melancholic type – monarchs, scholars and philosophers. However, for Goethe, colours weren’t just arbitrary symbols of these bodily states, they could also produce them. “Every colour,” he believed, “produces a corresponding influence on the mind.” Goethe tried to prove that colour had a direct, rather than mediated, effect on our feelings by tinting his laboratory windows alternately yellow, red, green and blue. He concluded that “the eye could be in some degree pathologically affected by being long confined to a single colour; that, again, definite moral impressions were thus produced… sometimes lively and aspiring [yellow], sometimes soft and yearning [blue], sometimes uplifted to the noble [red], sometimes dragged down to the base [green]”. His own house was decorated according to this scheme. Unpopular guests never made it past the “Juno room”, which was painted a “gloomy and melancholy” blue so that they wouldn’t be tempted to stay long. The lucky ones who had dinner invitations were led into the warmth of his yellow dining room: “The eye is glad-dened,” he hoped, “the heart expanded and cheered, a glow seems at once to breathe towards us.” He preferred to work in a green garden room as he found the neutral admixture of yellow and blue to be peaceful and soothing. Following Goethe, doctors began using colour not just as an aid to diagnosis, but as a cure in itself. The French psychologist Charles Féré, who worked under Charcot at the famous Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, was convinced of its psychological therapeutic properties. He began experimenting with coloured light on hysterics in the 1880s, glazing asylum cells with blue or violet glass to create calming and curative effects. Féré thought of coloured light as different waves or vibrations of radiant energy that could be sensed not just by the eyes, but all over the skin in a form of cutaneous vision. In 1887 he set up a device, invented by Etienne-Jules Marey, who pioneered the photography of serial motion, to test this peculiar theory. It was a primitive oscillograph which measured the contractions of the hand and forearm under the influence of various coloured lights, definitively proving, Féré thought, that red had the most exciting effect and violet the most calming. Other doctors had already followed Goethe’s lead. Dr Ponza, Féré wrote excitedly, “has announced happy effects from red light in melancholics and blue light in maniacs”, and Dr Davies, of the County Lunatic Asylum in Kent, “has obtained four cures of maniacs by the same treatment, but has not obtained any results in melancholics”. (However, Féré admitted, “the experiments of M Taguet had a negative result in all cases”.) Colour treatment soon became fashionable. The illustrations in Seth Pancoast’s Blue and Red Light: or, Light and its Rays as Medicine (1877) show a well-dressed woman sprawled languidly on a couch as she bathes in coloured light. One contemporary writer dubbed the resulting craze the “blue glass mania” and offered the following prescription: “Blue glass one part; faith, ten parts; mix thoroughly and stir well until all the common sense evaporates, as the presence of a minute quantity will spoil the mixture.” However, apparently lacking in common sense, the research conducted by scientists and physicians into the psychological power of colour inevitably influenced artists, who found in this work an affirmation of the moral significance and physiologic impact of their medium. Paul Gauguin’s use of bold, flat planes of non-representational colour, as seen in Faa Iheihe (1898), was directly inspired by chromo-therapy. “Since colour,” he wrote in his diary, “is in itself enigmatic in the sensations which it gives us (note: medical experiments made to cure madness by means of colours) we cannot logically employ it except enigmatically… to give musical sensations which spring from it, from its peculiar nature, from its inner power, its mystery, its enigma.” Kandinsky, who had been impressed by Gauguin’s forceful use of brilliant colour when he saw his paintings in Paris in 1902, came across chomo-therapy when he read Arthur Osborne Eaves’s The Power of Colours (1906). “Colour directly influences the soul,” Kandinsky wrote in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912). “Anyone who has heard of colour therapy knows that coloured light can have a particular effect upon the entire body. Various attempts to exploit this power of colour and apply it to nervous disorders have again noted that red light has an enlivening and stimulating effect upon the heart, while blue, on the other hand, can lead to temporary paralysis.”

That same year, the Swiss psychologist Dr Max Lüscher developed a colour test which consisted of a person sorting 73 colour patches into an order of preference (an abbreviated test of eight cards was also used), and claimed to be able to judge personality from the results. He even believed that “it is sometimes possible to deduce personality characteristics of a painter when great emphasis is placed on one or two colours, for example, Gauguin’s obsession with yellow in his later paintings”. His ideas served to boost interest in chromo-therapy, reviving a fashion just as the FDA was recalling all of Ghadiali’s devices. Lüscher was influenced by both Goethe’s theory of colour and Kandinsky’s neo-Romanticism – and thought his test worked as “an early warning system for stress ailments… cardiac malfunction, cerebral attack or disorders of the gastro-intestinal tract”. He was convinced colour had fixed primal associations that took us back to an ancient fear of the dark, to hunting and self-preservation. “The test is a ‘deep’ psychological test,” Lüscher asserted, insisting on its scientific veracity, “developed for the use of psychiatrists, psychologists, physicians… It is NOT a parlour game.” His theories were taken up not only by psychiatrists and therapists, but by the advertising and marketing industries, where they had a wider and more long lasting influence. For example, Lüscher advised that sugar shouldn’t be sold in a green package, as the colour is associated with astringence, whereas blue was associative of sweetness. In the 1960s, the American scientist Alexander Schauss read Lüscher’s musings on colour psychology, packaging and décor and began his own research into the physiological effects of colour. He thought he’d discovered a colour with a profoundly calming effect and was keen to put it to use. Beginning in 1979, he persuaded a number of American prisons to paint their cells a camp, but supposedly pacifying shade. If only he’d done so in time for Ghadiali’s confinement, the Bombay colour theorist might have found himself in a cell painted a bright Indian pink

|