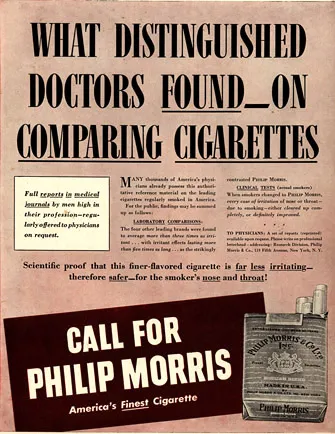

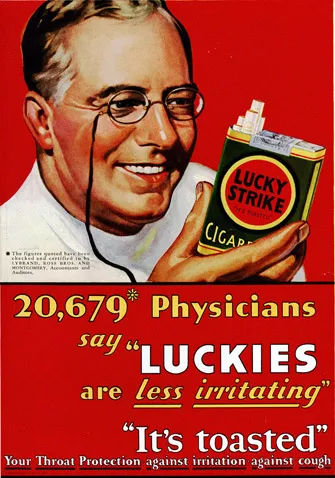

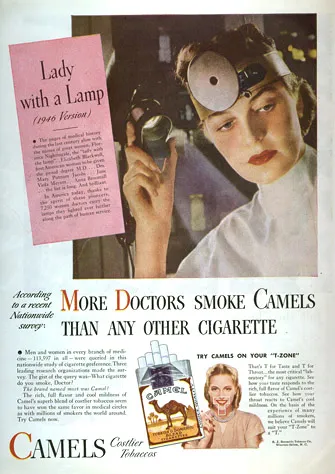

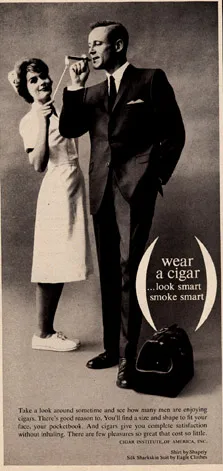

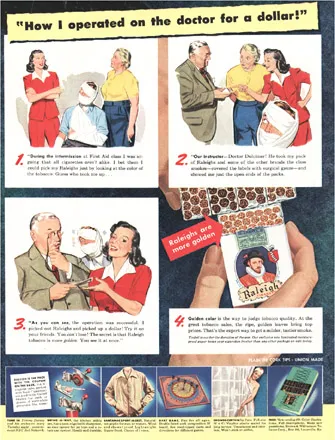

Images of the Noble Physician as a Smoker and Endorser of Cigarettes. One technique used by the tobacco industry to reassure a worried public was to incorporate images of physicians in their ads. The none-too-subtle message was that if the doctor, with all of his expertise, chooses to smoke a particular brand, then it must be safe. Unlike with celebrity and athlete endorsers, the doctors depicted were never a specific individual. The images were always of an idealized physician, wise, noble, and caring, who enthusiastically partakes of the smoking habit. Little protest was heard from the medical community or organized medicine, perhaps because the images showed the profession in a highly favorable light (the big push to document hazards also did not come until later). This genre of ads regularly appeared in medical journals such as the Journal of the American Medical Association, an organization which for decades collaborated closely with the industry. R. J. Reynolds made a name for itself by claiming that "More Doctors smoke Camels," following a campaign dreamed up by the William Esty Advertising Company to improve the brand's market share. The company paid for surveys to be conducted during medical conventions using two survey methods. Doctors were gifted cartons of camels at tobacco company booths and then were immediately asked to indicate their favorite brand. In another scheme, doctors were given free packs at company booths and then, upon exiting the exhibit hall, were asked what cigarette brand they carried in their pocket

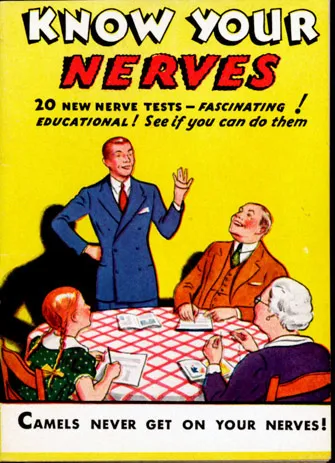

In a prime example of marketing wizardry, cigarettes were advertised simultaneously as both sedatives and stimulants, calming you when you are nervous, pepping you up when you are down. A champion sharpshooter endorsed camels because they "steadied his nerves." According to Camel ads: "Remember, you can smoke as many Camels as you want, their costlier tobaccos never jangle your nerves." Aside from keeping you keen and focused, they also relax and give pleasure. According to a relaxed-looking Rock Hudson reclining next to his pet collie, "It is important to smoke the most pleasure giving cigarette -- Camel." According to this ad, without Camels "you may yip like a terrier."

Cigarettes are Actually Good for You The audacity of the industry in the 1930s was such that they weren't satisfied just with denying health claims. Brand X, Y or Z was supposed to be "good for the throat," helping the T zone ("throat and taste"), etc. The RJ Reynolds Company went so far as to recommend cigarettes as an essential accompaniment of a good meal. "At mealtimes Camels offer a helping hand to good digestion" by "increasing the flow of fluids—alkaline digestive fluids—that are so vital to a sense of well being after eating."

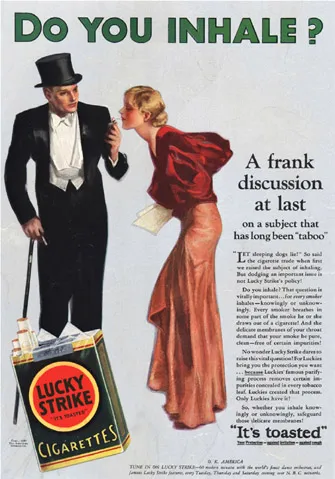

To Inhale or Not to Inhale: Is that the Question? American cigarettes made from bright leaf tobacco are milder than European types, and more easily drawn into the lungs. Licorice, cocoa, and many other sweeteners and flavorants are added. Non-inhalers were sometimes ridiculed

Well known early victims of oral cancer include Sigmund Freud who developed cancer of the palate after years of smoking 20 cigars a day and US Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Grover Cleveland

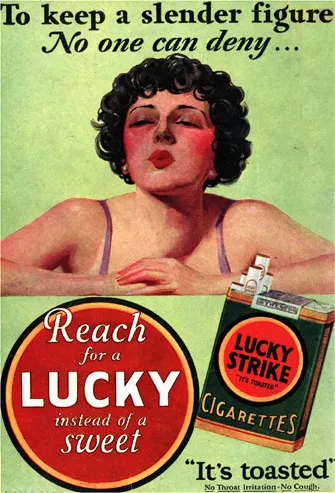

Launched in 1928, this highly successful campaign targeting women was eventually derailed by threats of litigation from the candy industry. The tobacco industry later promoted "candy cigarettes"

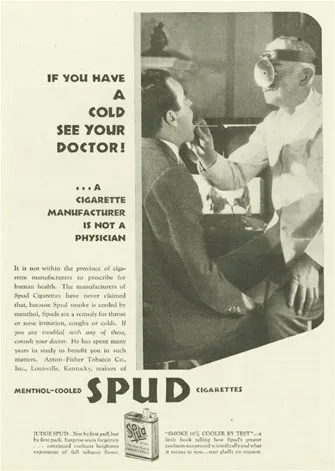

Menthol cigarettes were introduced in the 1930s. Menthol is a mint extract which triggers a sensation of coolness when it contacts the oral mucosa. Advertisers for these brands often touted their coolness as a contrast to the hotness of tobacco smoke. Marketeers later equated this coolness with freshness, a metaphor for healthfulness. Ads for menthol cigarettes often contained particularly outrageous health claims as typified by this Spuds Ad. In 2005, 27% of the cigarette market is for mentholated brands. 68% of African-American smokers use Kools, Salems, or Newports

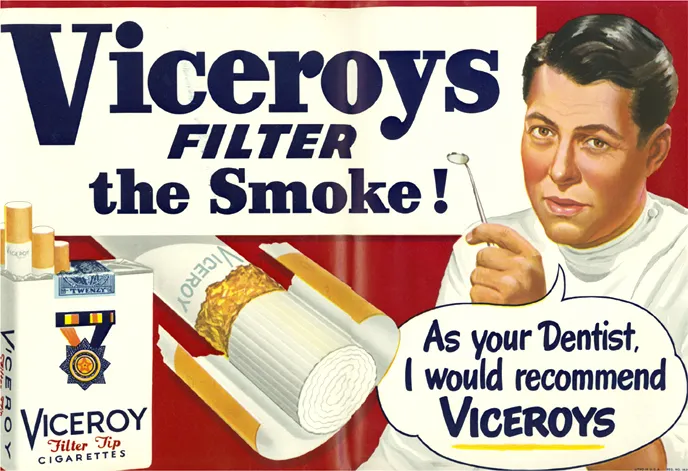

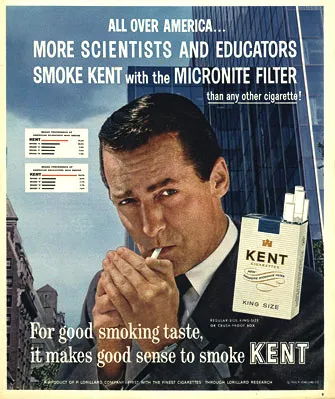

The Myth of the "Safe" Cigarette: Filters and "Health Reassurance" Cigarettes ("No other cigarette approaches such a degree of health protection . . .") Filters promoted health reassurance, but did little to reduce the hazards of smoking. Industry chemists were actually well aware that most filters actually removed no more tar and nicotine than the same length of tobacco would have! Madison Avenue nonetheless stepped up to the challenge of selling filters as the intelligent choice for smokers worried about their health: "The man who thinks for himself knows Viceroy gives you more of what you change to a filter for" - "You're so smart to smoke Parliament." - "More scientists and educators smoke Kent." Kent's Micronite Filter (Lorillard Tobacco Company) for at least 5 years in the 1950s contained crocidolite asbestos, one of the deadliest forms of this fibrous mineral. Smokers inhaled millions of deadly fibers per year and were never told of the hazard. Filtered brands nonetheless were a great success, growing in market share from 2 % in 1950 to 50 % in 1960 and 99% in 2005

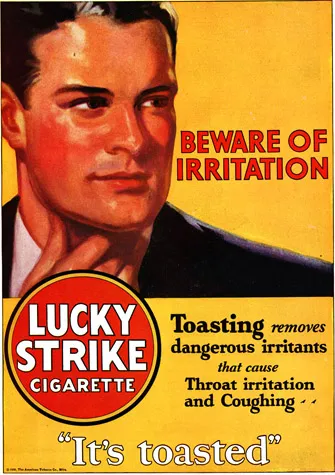

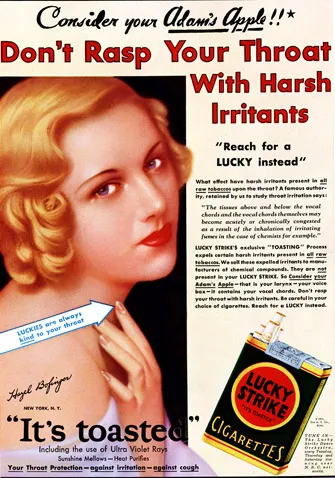

Freshness as a Metaphor for Healthfulness Tobacco ads are notorious for broadcasting what can only be called the "Big Lie" - and think about it: how could the inhalation of smoke of any kind be compared to "mountain air"? Smoke is offered as "fresh" and "clean"; smoking was supposed to be "springtime fresh" or make you "alive with pleasure." Ads such as these continued long past the 1950s, with verbal or visual themes of outdoor recreation, mountain air, clean rushing streams, and so forth. The freshness theme early on became grist for the industry's "tit for tat" advertising. So while Lucky Strikes were "Toasted" ("Sunshine mellows, heat purifies") Camels countered that their product was "Naturally fresh: never parched, never toasted!" Freshness was also commonly used as kind of code-word for healthfulness. Slogans used in tobacco ads called to mind the "cool" of ice or the fresh healing virtues of springtime mountain pastures. "Kool" and other menthol brands were also supposed to deliver a kind of hospital-like sense of sanitary safety, and one company implied cleanliness in its very name. "Sano" cigarettes didn't last very long: they didn't deliver as much in the way of tar or nicotine as more popular brands and their marketing skill lagged behind that of the bigger players. By contrast, menthol brands grew in popularity after the postwar "health scare," and many other forms of "health reassurance" were offered (space-age filters of myriad sorts, promises of low-tar and/or nicotine deliveries, eventually "lights," etc.

Before the First World War, smoking was associated with the "loose morals" of prostitutes and wayward women. Clever marketeers managed to turn this around in the 1920s, transforming cigarettes from symbols of decadence into symbols of women's independence. As part of this effort, the American Tobacco Co. in 1929 organized marches down 5th Avenue in New York of women carrying "Torches of Freedom" (i.e., cigarettes) to emphasize their emancipation. Early ad campaigns targeted at women included: "I wish I were a man" (so I could smoke, Velvet 1912) and "Blow Some My Way" (Chesterfield 1926). The industry sponsored training sessions to teach women how to smoke, and fashion shows to make women's attire match the green of Lucky Strikes packaging). Later brands such as Virginia Slims ("You've come a long way baby") were frankly exploitive of the womens' liberation movement. It is ironic that the Marlboro brand, famous for its macho "Marlboro Man" was for decades a woman's cigarette ("Mild as May," with 'Ivory tips to protect the lip') before it underwent an abrupt sex change in 1954. Only 5% of American women smoked in 1923 vs. 12% in 1932 and 33% in 1965 (the peak year). Lung cancer was still a rare disease for women in the 1950s; though by 2000 it was killing nearly 70,000 per year. Cancer of the lung surpassed breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer death among women in 1987

Many famous Hollywood stars appeared in cigarette ads in the 1930s through

the early 1950s; millions followed their screen idols’ lives and

tastes. A “smoker’s voice” was something to be cherished

by broadcasters in the 1930s and ‘40s, the era of radio. Smokers

developed a deep and mellow voice, and women who smoked were said to have

a more sensual, sexy voice. Throat cancer was well-recognized by the middle

of the nineteenth century, however; that was actually the primary meaning

of “smoker’s cancer” (or cancer des fumeurs) in this

earlier period. Throat reassurance was a common theme in American ads from

the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s. Popular singers (eg. Bing Crosby,

Nat King Cole), actors (John Wayne, Gary Cooper), comedians (W.C. Fields,

Jack Benny), and opera stars were hired to endorse particular brands as

gentle on the throat. Many dozens of celebrities who provided such testimonials

later succumbed to tobacco-related diseases such as emphysema, lung cancer,

or heart disease. Endorsements from athlete celebrities date from the second half of the nineteenth century, when cigarette manufacturers started inserting cardboard into cigarette packs to keep their smokes from getting crushed. Tobacco marketeers quickly realized that images could be put on such cards first movie stars, then athletes and military heroes, and eventually hundreds of other themes. Sports figures were sometimes paid for their services, but not everyone went along: Honus Wagner, the baseball star, was much opposed to smoking, and demanded that his image be removed from such cards—which is why his card now sells for 2-3 million dollars. The idea of cigarettes never getting your "wind" was an effort to counter the growing medical realization that smoking could actually make it harder for you to breathe. Emphysema was already a well-known pathology by the middle of the nineteenth century, and by the 1920s smoking was widely blamed not just for "pharyngeal catarrh" (mucus drainage down the throat) but for more general damage to the larynx and bronchial tubes, causing cough, hoarseness, bronchial catarrh and so emphysema of the lungs. Cigarette manufacturers wanted people not to think about such issues, and went out of their way to suggest that smoking would in no way compromise even an athlete&s ability to perform at his (or her) very best. Athletes from all realms of sport were paid to endorse specific brands -- this included baseball greats such as Babe Ruth, Lous Gehrig, and Joe DiMaggio, golf legends such as Ben Hogan, plus dozens of other heroes in football, basketball, tennis, swimming, bowling, and other popular sports. As late as 1947 cigarette manufacturers were able to harness experts to claim that smoking brand X, Y or Z did not compromise athletic performance. Sports-themed advertising continued into more recent decades, and as recently as the 1980s 26 out of 28 major league baseball stadiums had either Marlboro or Winston billboards in their outfields. Ads were barred from television in 1971, following which tobacco sponsorship of sporting events became commonplace: Reynolds established the Winston Cup NASCAR; Philip Morris created the Virginia Slims Women's Tennis Circuit and Marlboro Cup Horse Race; Benson and Hedges promoted Rugby and race car driving, and many other new ways to advertise were created (direct mail, personal gear, viral marketing, etc.).

The Tobacco Men also had an infatuation with brides, marriage, and its myriad associated symbols. Included here are dozens of blushing brides, cigarette in hand, decked out in full nuptial regalia

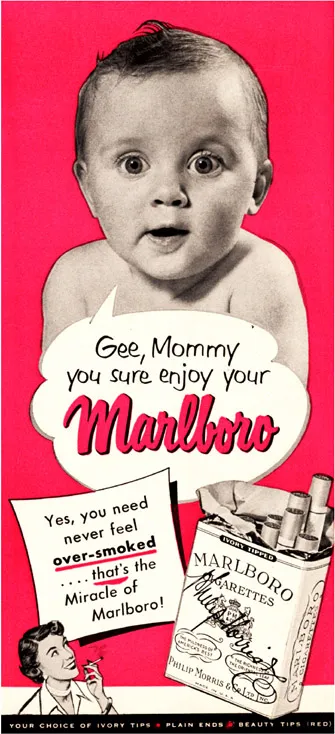

Gee Mommy, you sure enjoy your Marlboros Images of infants and children had multiple values to tobacco advertisers. They reinforced the respectability of smoking as part of normal family life. The images of youngsters tended to send a reassuring message about the healthfulness of the product. Finally, it was an obvious ploy as part of their campaign to expand the pool of women smokers.

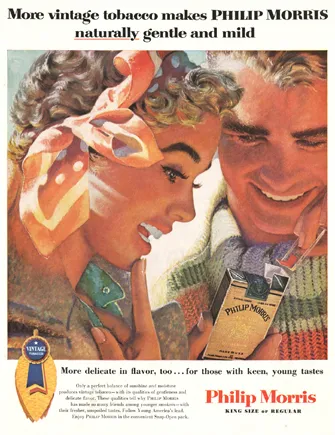

Gentleness and delicate flavor "These qualities tell why Phillip Morris has made so many friends among young smokers - with their fresher, unspoiled tastes." Smoking is not a habit often undertaken by adults. Almost all new smokers, the lifeblood of the industry, are teens and young adults aged 13 to 21. Internal company documents show that young people have been (and remain today) a key marketing target. Infants and children are often depicted in ads from the Golden Age of American cigarette advertising (1930s-'50s): a baby held tenderly in its mother's arms illustrates the gentleness of Philip Morris; another series has babies endorsing their parent's use of a particular brand. Still other ads show children gifting their dads with cigarettes on Father's Day. Teens were also a consistent target (internally characterized as "replacement smokers"): hence the ad copy that tells how Philip Morris "has made so many friends among younger smokers -- with their fresher, unspoiled tastes." A young man, with books cuddled under his arm and a pack in his hand, praises Chesterfields as "The largest selling cigarette in America's colleges." Graduates in cap and gown, holding cigarettes, were also used to identify, none too subtly, smoking as a proud badge of adulthood

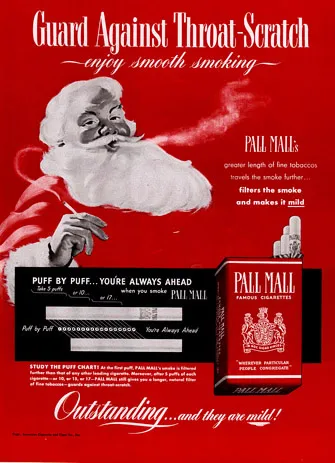

Cherished Icons in Tobacco Ads The tobacco industry made every effort to associate itself with noble institutions, patriotic themes, and cultural icons connoting respectability. Among the innumerable examples are: George Washington, Mt Rushmore, British royalty, the US flag, and the Statue of Liberty, the Capitol, referees, astronauts, and even the beloved family pet.. Even more prevalent were cultural symbols which brought to mind happy times and celebration. Our collection includes dozens of examples of ads featuring Santa Claus, often puffing away with obvious pleasure on one or another of the American Tobacco Company's cigarettes, cigars or pipes.

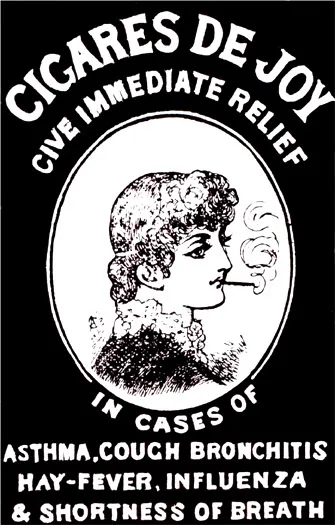

Health claims for tobacco smoking go back centuries. The Golden Leaf was in fact widely used as a drug: in the eighteenth century, for example, the police of Paris treated unconscious victims of drowning (pulled from the Seine but still alive) by forcing them to endure tobacco enemas. Nicotine was included in most European and American pharmacopoeia (official lists of approved drugs), a practice that didn't change until the twentieth century, when nicotine was deleted from the American Pharmacopoeia, just in time for the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Tobacco was excluded from the Act and henceforth "regulated" (such as it was) with liquor and guns in a new "Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms" established essentially as a taxation body. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, numerous firms advertised "asthma cigarettes" along with smokes intended as a soothing treatment for "Colds and Catarrh."

ads frequently appeared in the Sunday comics. Many were obviously targeted at young readers.

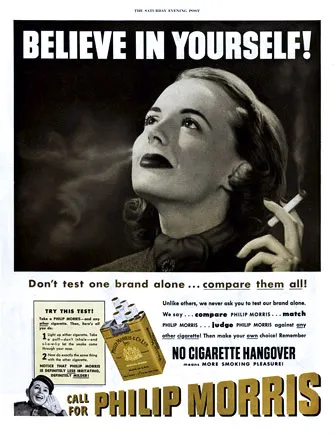

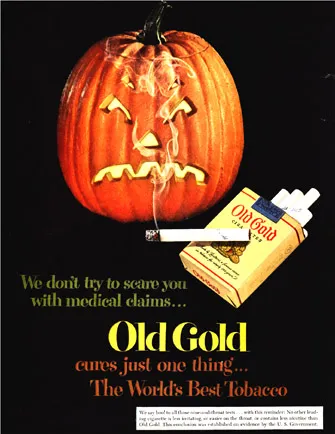

We Don't Try To Scare You With Medical Claims. . . Towards the end of the era in which false medical claims were endemic (early 1950s) the Old Gold brand had a prolonged campaign -- with more than 50 variations on this theme - in which they touted: "We Don't Try to Scare You with Medical Claims." Ironically, many of these ads in their fine print make outlandish statements that Old Golds were less irritating and thus safer than the competition. Somehow they calculated that the public would not see this obvious hypocrisy. Note the white box strangely reminiscent of the Surgeon General's warning introduced years later. In what can only be characterized as rank hypocrisy, they claim Old Gold's are less irritating and easier on the throat.

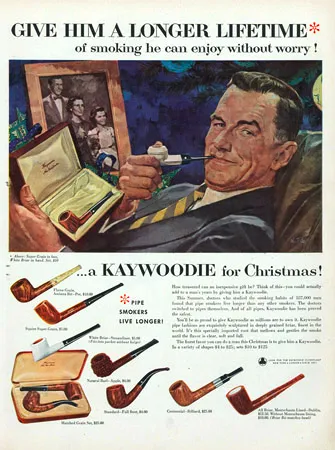

Give Him A Long Lifetime. How treasured can an inexpensive gift be? Think of this - you could actually add to a man's years by giving him a Kaywoodie. Doctors who studied the smoking habits of 137,000 men found that pipe smokers live longer than any other smokers

20,679 Physicians Say Luckies Are Less Irritating

|